“A Push for More Radical Conversations”: Rubinger Fellow Liz Ogbu on Building for Spatial Justice

Liz Ogbu, designer, urbanist and 2021 Rubinger Fellow, illuminates the ways our built environments have created and reinforced racial and class inequities. She’s also here to show us how communities can collectively envision—and enact—environments that repair the harms of injustice embedded, over the course of many generations, in the places we live and work.

Architecture and design are fundamental to the way we humans shape our environments. As an accomplished practitioner of these arts, Liz Ogbu is determined to design not just for aesthetics and utility, but in pursuit of an optimum goal: justice.

Architecture and design are fundamental to the way we humans shape our environments. As an accomplished practitioner of these arts, Liz Ogbu is determined to design not just for aesthetics and utility, but in pursuit of an optimum goal: justice.

Working around the country and the world, most often with people experiencing racial and economic oppression, Ogbu invites residents and users to be co-creators of design, recognizing they possess invaluable expertise about their own places, priority needs, and aspirations. Taking a long view of history, she wants to help communities begin to repair the harms of injustice embedded, over the course of many generations, in our built environments.

Ogbu has worked with women in Tanzania to adapt cook stoves to better suit their daily habits and cultural practices, and with immigrant day laborers to invent a comfortable shelter to replace the typically unmarked, unshaded lots where they wait for potential employers. Whether the space is a housing development, community park, or mini-plaza on an expanded sidewalk, she begins the work of change by listening and learning.

A recognized thought leader, Ogbu has taught at Stanford’s d.school and the University of Virginia School of Architecture, among others, and spoken widely. Her 2013 TEDx Talk and 2017 TED Talk have been viewed over a million times.

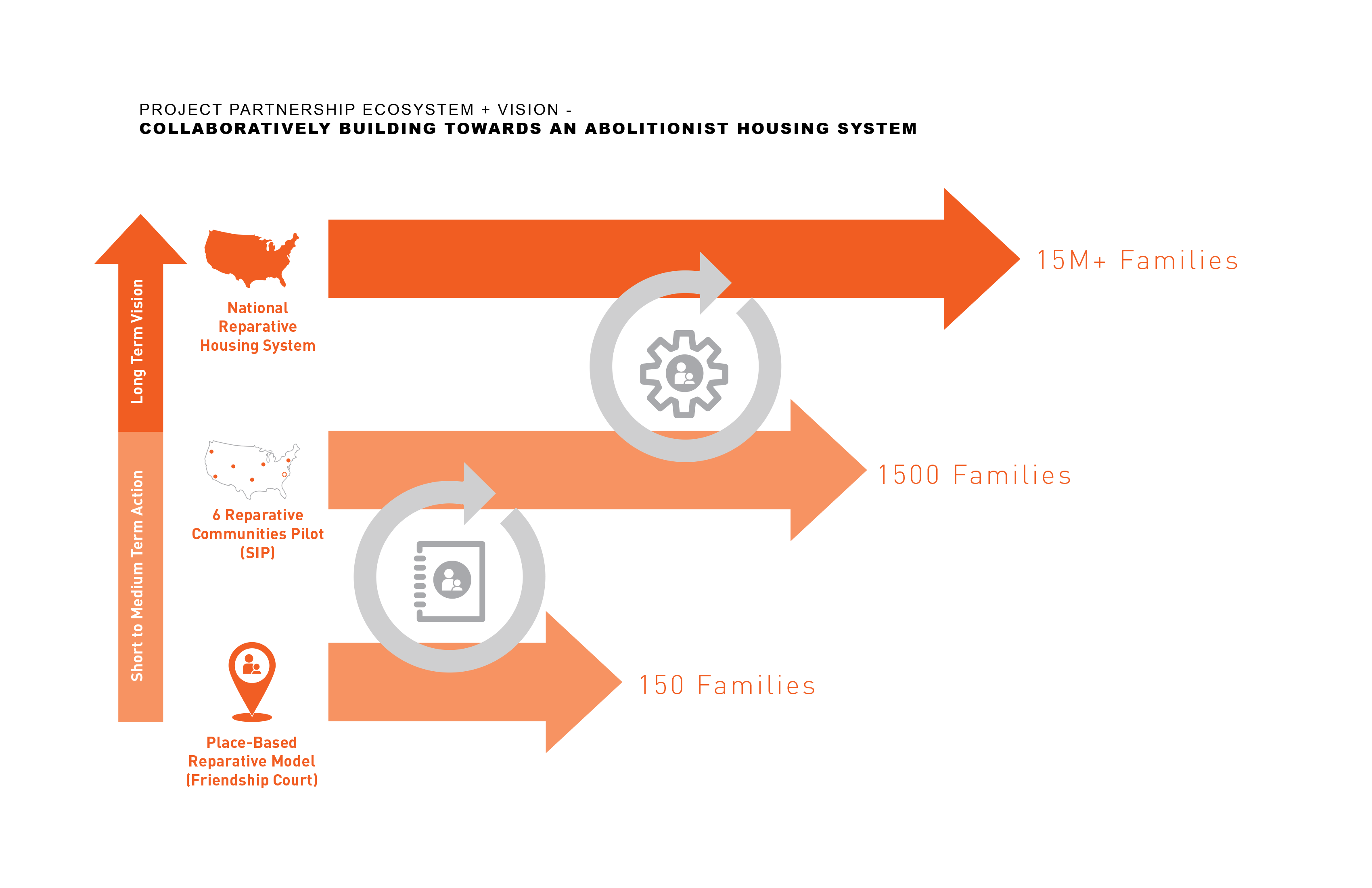

Ogbu’s Rubinger Fellowship has allowed her to advance work on an innovative Social Impact Protocol (SIP) that would be applied to the redevelopment of affordable housing, ensuring the process redistributes power to residents and achieves social goals beyond the rudimentary provision of shelter.

Ogbu and a partner in Tanzania working on a cooking stove prototype.

You’ve described America's conventional procedures for redeveloping affordable housing as “a system of normalized harm.” Can you elaborate on that?

I think that in conventional housing, especially affordable housing, we think what we really need to do is focus on producing units, to make sure we get as many people as possible housed.

That is fine, but if that's all that we do, then we're not doing much to make a dent in the systems that create the conditions in the first place. If we just have units as our goal, then we're participating in a system that is keeping people poor.

Take one of the projects I have been working on for the last five years, Friendship Court in Charlottesville, Virginia. We’ve done the work to enable residents to operate as co-owners and co-decisionmakers in the process. I've done a lot of interviews with residents. And what they've said to me is, here's the thing: So we have better housing. That housing is not their aspiration for where they want to land in life. Having a new unit is awesome because it means less issues, more space, etc., but that doesn't actually secure their ability to get a better job. It doesn't change their ability to get better childcare for their kids or make sure that their kids can do better in school. All of the conditions that keep them poor remain, even though they have a new building that surrounds them.

Tell us a little about how your Social Impact Protocol (SIP) would redirect this process in the way you’re talking about.

The protocol is still in a pilot phase, but we’ve worked with researchers across a variety of issue areas to look at, well, what are the things that we need to think about in the context of projects that are explicitly aimed at breaking the loop of poverty? So looking at education, what are the stats we need to know? If we look at the eighth grade math score, what does that tell us in terms of the opportunities or the outcomes that are going to happen? Or how do we look at health outcomes? And how do we start to consider this stuff earlier on? It’s going beyond what we typically do in assessing a building project at the beginning—like do the financials pencil out and what are the site conditions.

The other key component of the SIP is, how do we actually create a system in which the residents can function as co-decisionmakers? It’s not just the default “oh, we're going to have a few community meetings and check the box” but actually building up a power base with residents so they can also have a seat at the table in a really meaningful way.

Where will this happen first, in individual developments?

What we're hoping to do is to pilot this in a couple of LISC cities, and then work in collaboration with development projects that are happening there. So, it would be the SIP team, the local LISC office, the (likely) nonprofit developer, and then part of the process would be building up the capacity and power of the community clients as well.

When you talk about “repair,” it seems you’re tying physical change to the idea of racial reparations—restitution for communities that have been marginalized and mistreated for a long time.

A lot of the ways in which reparations get talked about is in terms of financial compensation, which, to be clear, I totally think is important. But if we just get cash payments, again, we're actually doing nothing to change the system, to create different opportunities and outcomes for the generations to come. I think we also need to look at place-based reparations.

When I started working on Friendship Court, I had countless people around town being like, “This is going to be like a Vinegar Hill,” which was in the major African-American neighborhood that was razed during urban renewal. And Friendship Court itself was created by another urban renewal act that cleared other African Americans away to build this superblock of racialized poverty.

We were trying to talk about all these amazing things we're going to do, and people were still stuck with, oh no, I remember the last time people said that.

Just because we're investing now, does it mean that we've healed everything that's happened before? Unless we have that lens where we also look at the before times, it makes it really hard to make sure that as we look to the future, we're taking into account everything that needs to be considered.

Ogbu's plan for scaling a reparative community vision of housing

Ogbu's plan for scaling a reparative community vision of housing

So in the long run the SIP concept might be applied to other forms of community development— parks, community facilities, business corridors—and maybe one day broadened as some type of overall rubric for development in general?

Yes, I think so. With folks at the University of Virginia, which has been hosting the SIP project, one of the things that we've been talking about is, can we convene folks working in different cities who are looking at different project types like the ones that you mentioned.

I think housing is just the first bite of the apple, and I could see the SIP ultimately being part of a larger framework. The initial idea for this protocol actually came from Marc Norman, a policy and economic development guru with a justice lens. We were working together on Friendship Court when he said, “Part of my scope is supposed to be financial feasibility analysis/market analysis, but what all these projects really need is a social impact analysis.” We should place as much importance on social impact to determine a project’s viability.

So I do think there is a valid argument to having this become a core part of “business as usual”—every project – housing and beyond - does this, and it works in concert with the other things that we know are part of what’s required to be able to build something.

You call yourself a spatial justice activist. That’s such a powerful expression. Can you trace some elements of what spatial justice looks like?

At its basic level, it means we have freedom from the idea that the amenities, resources, opportunities, and even outcomes that we can access are dictated by the color of our skin, the wealth of our family, or any identity that otherizes us in the context of the dominant identities in the systems of oppression.

It means that I could run some of the data sets that we've talked about in the Social Impact Protocol, like life expectancy, and see no difference based on zip code. “Undesirable” uses don't get lumped up in the Black neighborhood and a kid coming home to an affordable housing project has just as much opportunity in life to attend a good school, to be able to get to college, as a kid who's living in a nice suburban home.

We see examples of what the lack of spatial justice looks like when you have differences in which some communities wind up with the multi-million dollar transit center versus the insufficient bus routes, or the really lovely parks versus lots of vacant lots. And when you overlay demographics, it's very clear to see who got the good things, and who didn't.

I think that the larger fight around civil rights and achieving equity is actually fundamentally impossible if we still don’t have our cities and places contributing to each of our well-being, regardless of identity. We will never get free if we continue to be separated and selectively harmed by space.

What’s more, something that I've been seeing a lot through the trauma and healing work that I've been exploring, is that when it comes to racism, injustice, and spatialized harm, we're actually all victims of it, regardless of whether you're a person of privilege or not.

There's a cost to living in a society that operates in the way that ours does. You may be somebody who has some means, who lives in a house where you're not fearing violence, where you know that your water will turn on and be safe to drink, etc. For a lot of us who live in those conditions, we feel a certain sense of guilt. But we just keep on moving on because we accept that this is the way it is. And we're just trying to do the best that we can.

Unless we have a reckoning with the ways in which we’ve lost some part of ourselves, the ways in which we make certain compromises and the trauma that is associated with that, I don't know that it becomes possible for us to hold space for all of these other traumas.

Is there anything you’d like to add?

I'm definitely not under the illusion that the Social Impact Protocol is a panacea. For me, the impetus for that, and for the work I do in general, is that if we don't start working towards rectifying these systems, they won’t get fixed.

The tweaks we often do just improve the systems slightly, but they don't actually save any future generation from dealing with the things that compel a lot of us to do this work. And so, this is a push for more radical conversations about what it is that we're responding to and what does success really look like.

Within a number of Indigenous cultures, they talk about the seven-generation view. I'm under no illusions that these systems get completely fixed before I die. But I want to know that in this leg of the race that I'm running, I’m doing as much as possible to set up the next generation to hopefully be able to tear down this system and manifest a vision in which every one of us is surrounded by healing spaces that support their capacity to thrive.