The Rural Opportunity and Development Series of Virtual Sessions

The ROAD Series of Virtual Sessions is a series of virtual exchanges co-designed and hosted by the Aspen Institute Community Strategies Group, the Housing Assistance Council, Rural Community Assistance Partnership and Rural LISC.

The ROAD Seires of Virtual Sessions will highlight and unpack rural development ideas and strategies that are critical in response to COVID-19 and to long-term rebuilding and recovery. Each month, the ROAD Sessions will feature stories of a diverse set of on-the-ground practitioners who have experience, wisdom and savvy to share. The series will reflect and emphasize the full diversity of rural America, spotlight rural America’s assets and challenges, and lift voices and lived experience from a wide range of rural communities and economies. Each Session will include an added opportunity for peer exchange. Overall, ROADS aims to infuse practitioner stories and lessons into rural narratives, policymaking and practice across the country, and to strengthen the network of organizations serving rural communities and regions.

ROADS is the first of several pieces of content being developed collaboratively between these organizations, with a goal of lifting up conversations around rural economic prosperity and redefining what rural economic development looks and feels like in the future.

Session 1 - Still Open for Business: Working with Minority-Owned Rural Firms through the Pandemic.

Racially and ethnically diverse populations comprise 21 percent of rural America—but produced 83 percent of its growth between 2000 and 2010, a trend that has continued since. Along with that, enterprising Latinx, Black and Indigenous entrepreneurs are launching businesses bringing new life to many rural communities – and creating better livelihoods for their owners and employees. But what has happened to these firms during the COVID-19 crisis? And how are rural development organizations adapting what they do to help these firms to get through the emergency and recover?

In this first Rural Opportunity and Development (ROAD) Session, rural minority business owners detailed their recent experiences, in partnered conversation with the regional intermediaries who have been helping them with technical assistance, funding and advocacy.

Session 2: DESIGNING SCALABLE CO-FUNDING SOLUTIONS FOR BROADBAND AND DIGITAL EQUITY

On December 12, 2023, the ROADS collaboration hosted a panel at the annual Rural LISC Seminar to help rural communities understand and participate in the new federal funding available for high-speed broadband internet. Widely viewed as a once-in-a-generation investment in closing the digital divide, the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law’s package of broadband infrastructure deployment and adoption subsidy programs administered by NTIA, along with additional sources from USDA and FCC, are explicitly rural-facing with $62.4B available over the next five years to address rural connectivity gaps.

While the current round of investment in broadband is centered on local decision-makers for the first time in the history of public subsidy for telecommunications, the panel – Benya Kraus Beacom, co-founder of Lead for America, broadband planning consultant Brian Rathbone, principal of Broadband Catalysts, Jerry Kenney, program officer for the T.L.L. Temple Foundation, Zaki Barzinjii, senior director for Aspen Digital, and Christa Vinson, moderator, and Rural LISC’sbroadband lead – emphasized the deep need for fresh thinking and strategies from ecosystem players to better marshal local capacity to maximize capital absorption for broadband — and beyond.

BROADBAND PRESENTS UNIQUE CAPACITY CHALLENGES COMPARED TO OTHER RURAL INVESTMENTS

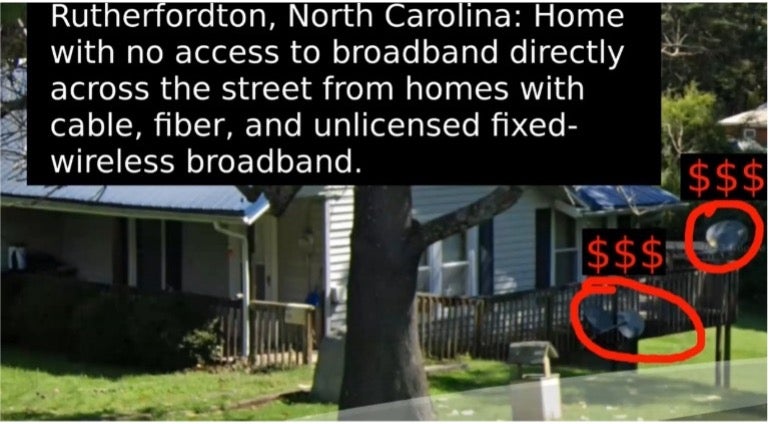

Despite significant improvements to federal broadband availability datasets, local communities – and individual residents – will have to self-advocate to ensure available public funding reaches every unconnected home. Brian Rathbone, who described a passion for digital equity that formed when he realized he could teach himself using the internet, every community in the country will encounter “embedded digital inequity,” where neighboring houses on the same block have access to different levels of service – or no access. “We have to accept the fact that many of these problems we do to ourselves structurally,” he said. Last-mile broadband dollars won’t get allocated to households in an area that’s indicated as served. Providers are reticent to share infrastructure and risk customer loss or expand a network to neighborhoods where the uptake has been historically low.

The great risk is these differences become deeply entrenched: “Communities can look different but at the end of the day the impact of digital inequity is the same,” said Zaki Barzinjii. “It means your community is ‘other-ized.’ It means you’re kept from the same types of opportunities and economic success than other communities are.” However, there are workable strategies to expose and resolve the underlying “othering” that marginalizes too many communities.

As Benya Kraus Beacom noted, pointing to the Lead for America network she co-founded of more than 200 field-based national service members who are “[anchoring local capacity] to the people that the community already trusts,” promising practices abound. She describes the patient building of “ecosystems of digital adoption leaders” that have led to real project capitalization and implementation. Among them: the formation of broadband action teams of cross-sector organizations creating a mission statement of digital equity for “our place” – whether that’s a low-to-moderate income residential community, or including digital inclusion as a baseline component of intake for human service organizations, or surveying “farm to farm” to subsequently launch a campaign, ‘We Believe in a Fiber Future,’ that helped arm a Minnesota local government with the evidence needed to justify the match dollars to compete for a state subsidy for broadband.

“As we tried to encourage a whole generation of people to move back to their rural communities [through Lead for America], access to broadband was one of the cornerstone challenges of how you scale and support talent returning home. We saw that if we’re going to try to do anything around economic development and rural prosperity, we would have to tackle this digital divide.”

— Benya Kraus Beacom, Lead for America Co-founder

For Lead for America, solutioning for broadband meant recognizing that technical assistance isn’t just about getting someone to write the grants, but “investing in the trust-building, the public pressure and awareness, even, that this is an urgent investment.” That comes first. Once organizations that didn’t see themselves as the backbone or champion for digital equity begin to recognize it as “their issue” and start incorporating it, new opportunities can follow.

This rural home has satellite and is paying more for lower quality internet and television service, while cheaper cable and fiber service is available across the street. This house is considered served and wouldn’t automatically be considered for current subsidy programs. For circumstances to change, this household “would have to be able to afford it and know they wanted it,” said Rathbone.

“ENTRY POINTS AND NO DEAD ENDS”

The panel’s other key insight was the very specific role philanthropy and adjacent funders can play. The process-driven stakeholder engagement and long timelines that constitute successful broadband deployment can in themselves provide the architecture for a new civic agenda – in other words, highly technical broadband projects cannot and should not be separated from the civic, institutional and capacity challenges rural communities that need broadband also face. Getting the dollars absorbed and managed correctly necessitates a creative formula of place-based institutions driving positive change, their reach extended by high-capacity intermediaries, as Temple Foundation has done to address myriad local concerns from broadband and water to child education and nutrition.

“We need expertise at a regional level at least – across all areas rural communities are dealing with — and simultaneously. Every time we invest in physical infrastructure like broadband without investing in the capacity of our institutions to do this work, we’re taking from what already exists, which is very minimum, and has been eroding over time. We have to be catalytic: these are billion-dollar challenges, and we have millions. There’s no million-dollar solution to billion-dollar challenges. At the heart of all of this sits capacity: how we’re defining it, how we’re investing in it. If we fund something by ourselves, we’re probably doing it wrong.”

— Jerry Kenney, T.L.L. Temple Foundation

Standing up durable collaboratives takes time, while philanthropy can adapt – and at the same time be selective. As Jerry Kenney explained, rural philanthropy could focus entirely on “downstream” socioeconomics impacts but – especially as it comes to operationalizing available broadband funding – the Temple Foundation and its peers are turning attention upstream. There’s not enough funding for the activity itself (broadband deployment) but philanthropy can resource the “system that does the thing,” he said.

This can involve launching new institutions. Looking to overcome structural disadvantages by filling in the missing tools or institutions, East Texas made ecosystem-enhancing investments that would sustain institutions over time; the foundation attracted three Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs) to the region where just three years before there were none. This was a purposeful choice over zooming in too closely and, for example, making a handful of small business loans.

“This is about the prioritization and sequencing, but we have to turn these problems around and think in terms of decades not months,” Jerry Kenney concluded. We have to “move away from projects and towards pathways.”

This summary originally published by the Aspen Insitute Community Strategies Group.